Have you ever been bothered by the idea of career batting averages, how it doesn’t reflect a player’s form, and how it’s unfair to compare averages of cricketers who’ve played over a hundred tests to cricketers who’ve played maybe thirty since one bad innings will damage the experienced cricketer’s average way less than the relative newcomer?

Well, you’re not alone. I’ve always thought that cricinfo should report a ten-innings rolling average. Occasionally you get a stat like “Cook is averaging 60 or so in the last few matches” or whatever, but there’s no functionality on cricinfo or statsguru to be able to look that up.

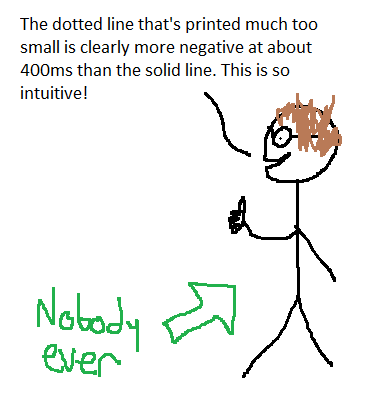

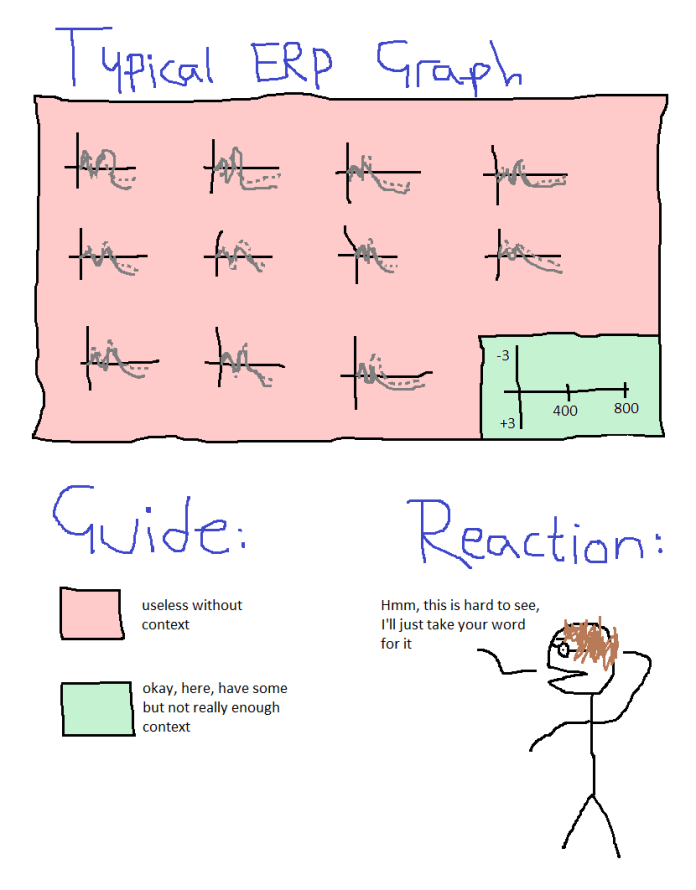

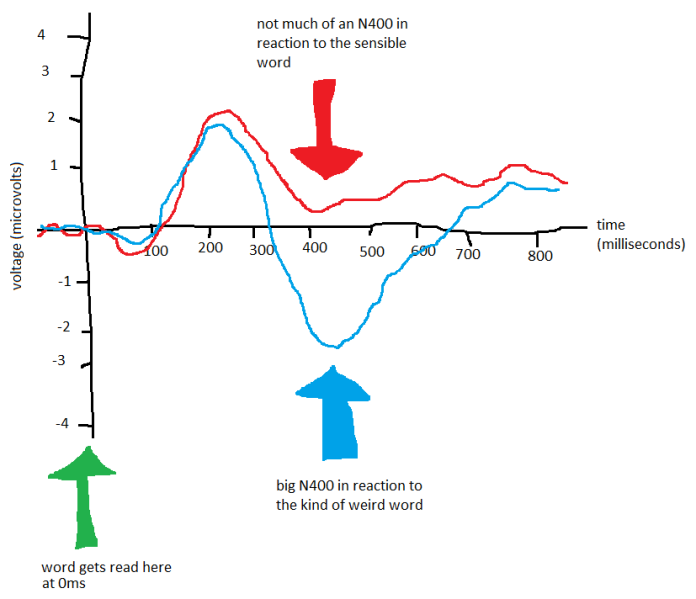

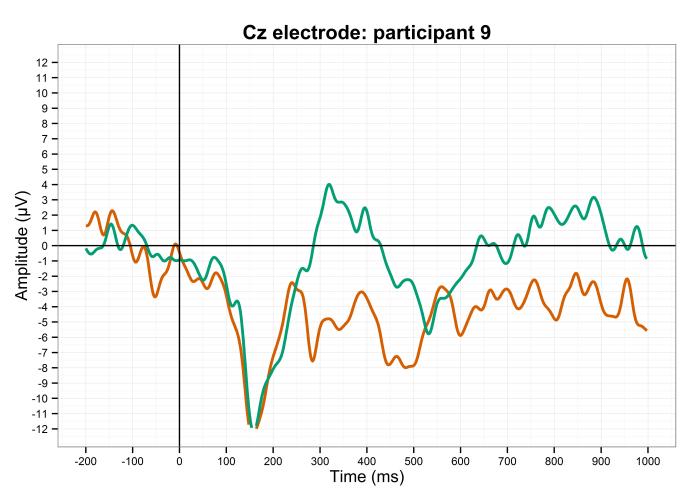

Enter R. R is a free open-source statistical programme that I normally use for my ERP research, but it’s also the next best thing after Andy Zaltzman for settling arguments about cricket statistics.

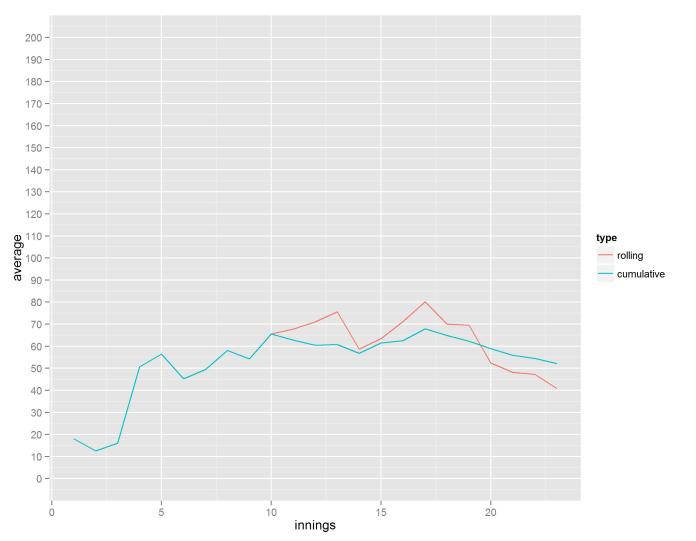

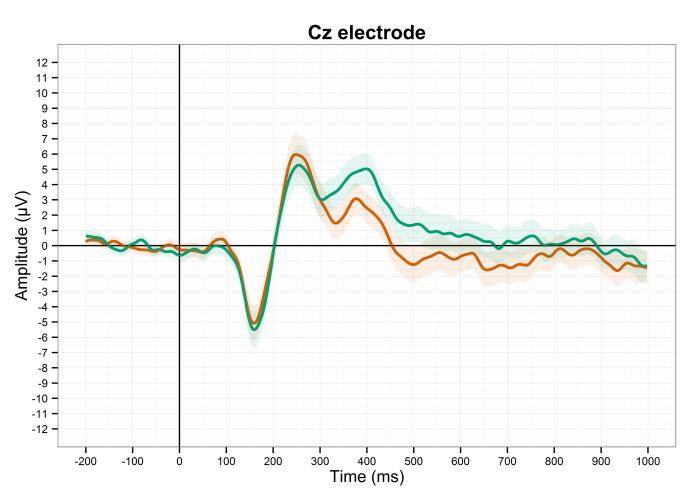

I’ve written some R code which can take any cricketer on cricinfo and spit out a ten-innings rolling average to show fluctuations in form. Plotting it with ggplot2 can show a player’s peaks and troughs as compared to their career average, and can hopefully be used as a much more objective way of saying whether or not somebody’s playing badly.

Alastair Cook has been a lightning rod for criticism in the last couple of years. He scored heavily in his first few matches as England captain, and for a little while it seemed as though captaincy would improve his batting, but then he went into a long slump. He recently broke his century drought, and people are divided over whether he’s finally hitting form again or whether this is a dead cat bounce on an inevitable decline. Some people take his last five Tests and say he’s back; others take his last year or two in Tests and say he’s lost it. What is missing from all the misspelled derision in the comments under any article about Cook is a ten-innings rolling average and how it changes over time.

This graph shows Cook’s peaks and troughs in form quite nicely. The big one in the middle where he averaged about 120 over ten innings is a combination of his mammoth 2010-11 Ashes series and the home series against Sri Lanka where he scored three centuries in four innings. His recent slump can be seen in the extended low from his 160th innings and onwards, where his rolling average went down to below 20. Now, though, it’s clear that not only has he regained some form, he’s actually on one of the better runs of his career.

Similarly, it seems like commentators and online commenters alike feel like Gary Ballance should be dropped because he’s on a terrible run of form. Certainly, he’s had a few disappointing innings against the West Indies and New Zealand lately, but is his form that bad?

…no, no it isn’t. He’s still averaging 40 in his last ten innings.

If anything, it’s Ian Bell who should be dropped because of bad form:

Bell’s average has had a few serious drops recently, going down to 20 after a poor Ashes series in Australia (along with pretty much every other England player too), rebounding a bit after a healthy home series against India, and then plummeting back down to 20 after two bad series against West Indies and New Zealand. Unlike Cook, however, Bell never seems to stay in a rut of bad form for very long… but that never stops his detractors from claiming he hasn’t been good since 2011.

The missing bit in the cumulative average line, by the way, is from where Bell averaged a triple Bradman-esque 297 after his first three innings against West Indies and Bangladesh, which were 70, 65*, and 162*.

The forthcoming Ashes series also raises the interesting comparison of Joe Root and Steven Smith, two hugely promising young batsmen both at their first real career high points. Smith in particular is seen as having had an excellent run of form recently and has just become the #1 ranked Test batsman. Most cricket fans online seem to think that there’s no contest between Smith and Root, with Smith being by far and away the better batsman…

…but it appears that there’s not actually much to choose between them. If anything, Root has had the highest peak out of the two of them, averaging 120 over ten innings against India last summer and the West Indies more recently (this is in fact comparable to Alastair Cook’s peak against Australia in 2010-11, but has attracted far less attention). He’s dropped a little since, but is still averaging a more than acceptable 85. Smith’s current rolling average of 105 is also very impressive, and it’ll be fascinating to see how he gets on in this series.

If you are interested in calculating and plotting these graphs yourself, you can follow the R code as below.

Firstly, if you don’t use them already, install and run the following packages:

install.packages('gtools') install.packages('plyr') install.packages('ggplot2') install.packages('dplyr') install.packages('XML') require('gtools') require('plyr') require('ggplot2') require('dplyr') require('XML')

The next step is to create a dataframe of innings for each player. You can do this by going to any player’s cricinfo profile, and then clicking on “Batting innings list” under the statistics section. Take that URL and paste it in here like so:

This creates a fairly messy dataframe, and we have to tidy it up a lot before doing anything useful with it. I rolled all the tidying and calculating code into one big function. Essentially, it sorts out a few formatting issues, then introduces a for loop which loops through a player’s innings list and calculates both the cumulative and ten-innings rolling averages at each individual innings (of course, the first nine innings will not return a ten-innings rolling average), and then puts the dataframe into a melted or long format:

rollingbattingaverage <- function(x) { x$Test <- x[,14] # creates new column called Test, which is what column 14 should be called x <- x[,c(1:9, 11:13, 15)] # removes 10th column, which is just blank, and column 14 x$NotOut=grepl("\*",x$Runs) #create an extra not out column so that the Runs column works as a numeric variable x$Runs=gsub("\*","",x$Runs) #Reorder columns for ease of reading x <- x[,c(1, 14, 2:13)] #Convert Runs variable to numeric variables x$Runs <- as.numeric(x$Runs) #This introduces NAs for when Runs = DNB x <- x[complete.cases(x),] rolling <- data.frame(innings = (1:length(x$Runs)), rollingave = NA, cumulave = NA) names(rolling) <- c("innings", "rolling", "cumulative") i = 1 z = length(x$Runs) for (i in 1:z) { j = i+9 rolling[j,2] = sum(x$Runs[i:j])/sum(x$NotOut[i:j]==FALSE) rolling[i,3] = sum(x$Runs[1:i])/sum(x$NotOut[1:i]==FALSE) } #because of the j=i+9 definition and because [i:j] works while [i:i+9] doesn't, #creates 9 extra rows where all are NA x <- rolling[1:length(x$Runs),] #removes extra NA rows at the end melt(x, id="innings") }

Then I have another function which sorts out the column names (since changing the names of a function’s output is kind of tricky) and adds another column with the player’s name in it so that the player dataframes can be compared:

sortoutnames <- function(x) { x$player = deparse(substitute(x)) allx <- list(x) x <- as.data.frame(lapply(allx, 'names<-', c("innings","type", "average", "player"))) }

Now we can plot an individual player’s rolling and cumulative averages:

The next function isn’t really necessary as a function since all it does is rbind two or more dataframes together, but it makes things easier and neater in the long run:

And finally, we need to create functions for various types of graphs to be able to compare players:

plotrolling <- function(x){ myplot <- ggplot(data=x[x$type=="rolling",], aes(x=innings, y=average, colour=player)) myplot+geom_line()+scale_y_continuous(limits=c(0, 200), breaks=seq(0,200,by=10)) } plotcumulative <- function(x){ myplot <- ggplot(data=x[x$type=="cumulative",], aes(x=innings, y=average, colour=player)) myplot+geom_line()+scale_y_continuous(limits=c(0, 200), breaks=seq(0,200,by=10)) } plotboth <- function(x){ myplot <- ggplot(data=comparisons, aes(x=innings, y=average, colour=player, size=type)) myplot+geom_line()+scale_size_manual(values=c(0.6,1.3))+scale_y_continuous(limits=c(0, 200), breaks=seq(0,200,by=10)) } plotrollingscatter <- function(x){ myplot <- ggplot(data=x[x$type=="rolling",], aes(x=innings, y=average, colour=player)) myplot+geom_point()+scale_y_continuous(limits=c(0, 200), breaks=seq(0,200,by=10)) }

Now that all the functions exist, you can get the information quickly and easily; just find the correct URL for the player(s) you want, paste it in the bit where the URL goes, and then run the functions as follows:

Root <- rollingbattingaverage(Root.full) Root <- sortoutnames(Root) plotplayer(Root) comparisons <- compareplayers(Root, Smith) plotrolling(comparisons) plotcumulative(comparisons) plotboth(comparisons)