Picture the scene: You’re a football manager. You’re in charge of a big club with a good youth academy, and you want your academy players to succeed. Good prospects need playing time… but you’re chasing the Champions League positions, and you can’t guarantee a starting slot for your promising but unproven 19 year old. You could loan him out to a smaller team so he gets game time… but good prospects also need to learn from watching the best at work, and your 19 year old won’t pick up the highest level tips and tricks on a League One training ground.

It’s a dilemma. Do you loan him out for game experience and deprive him of the chance to study with the best, or do you keep him around the squad for the learning opportunities and deprive him of the chance to learn how to adapt to match situations?

As a Charlton Athletic fan, my instinct is to say loan him out. Despite Duchatelet’s concerted efforts to completely ruin us, we’ve got one of the best academies in the country, and the big clubs are often hovering around, ready to swoop. I certainly can’t begrudge our players moving on to bigger and better things, but it seems that our players stall once they get to big clubs and stop playing so much. Jonjo Shelvey, for example; he was running our midfield in League One, but it felt like he went backwards once he got to Liverpool and spent all his time on the bench. Surely, many of us felt, it would be better for Liverpool to have loaned him straight back to Charlton; we’d have had an excellent player getting us into the Championship, and they’d have had a player gaining valuable match experience.

This is all just post-match pub conjecture, but luckily, there’s the internet, which is basically an all-you-can-eat buffet of sports numbers. So I’ve been mining the Charlton Athletic youth team page on transfermarkt to extract playing data for all our academy footballers over the years.

Writing the code for this took many, many hours. Unlike cricinfo, the site isn’t configured in a very scrape-friendly way… but hey, it was an amazing regex workout. I’ll post a 700-odd line script another time.

Once you’ve got a lot of data, you can do all kinds of stuff with it. The difficult thing is asking the right questions.

What I want to know is whether more playing time as a young player is related to greater success later on. Measuring “success” as a footballer is a very vague notion, so let’s refine it a bit:

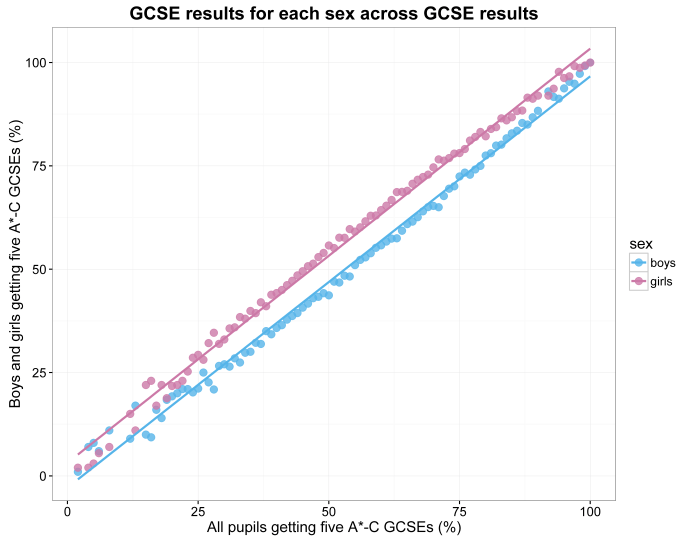

Does playing more games at any level when under 21 mean playing more games at the top level when over 21?

I’m going to arbitrarily define “top level” here as the English Premiership, Spanish La Liga, Italian Serie A, German Bundesliga, French Ligue 1, as well as Champions League and UEFA Cup / Europa League matches. Feel free to argue with me in the comments!

This is a lot easier to work out. We also have to refine it to looking at players who are already over 21 so that we’ve got post-21 career success to look at. This means not including players like Joe Gomez because he’s still only 19, so his 31 under-21 appearances and 0 over-21 appearances will through the data. I’ve limited it to players who are currently older than 24, with the opportunity for at least three full seasons aged post-21. Also, this analysis does not include goalkeepers, as the higher competition for places means that many second-choice goalkeepers never play at all.

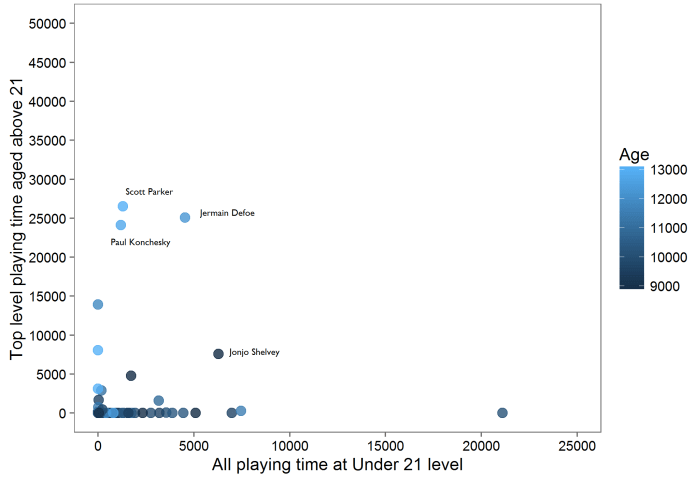

Right, so let’s look at my intuition:

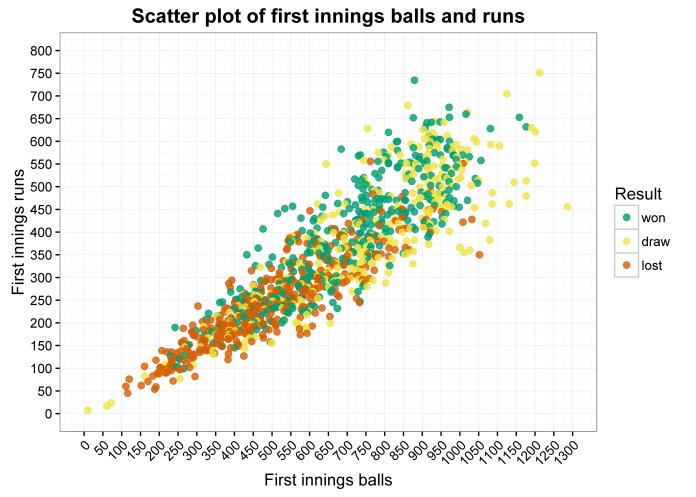

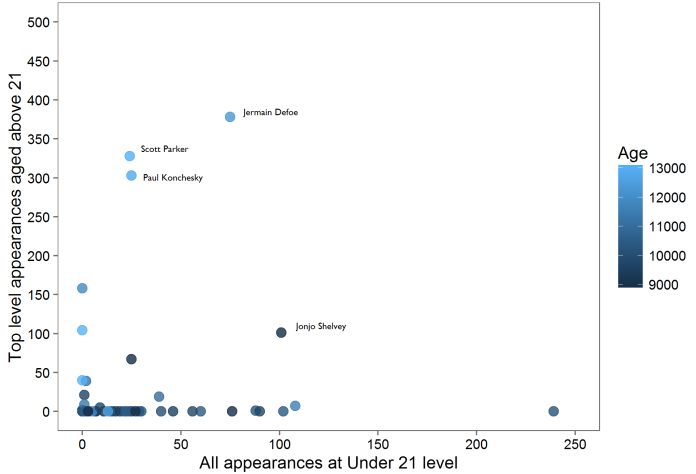

…my intuition isn’t very good. There’s no relationship between how many games a player features in and how many top level games that player features in (r = 0.05, p = 0.74).

(Age on the graph is expressed in days, by the way. Leap years make time calculations hugely frustrating.)

It could be that these correlations are thrown off by lots of late substitute appearances; you technically count as making an appearance regardless of whether you play the entire game or come on at 89 minutes to run down the clock.

So, I repeated it for actual number of minutes played… and it’s the same kind of picture (r = 0.0, p = 0.99):

It looks like my feeling about youth game experience being related to future success is inaccurate. But, this is pretty small data, taken from one club’s youth team players. It could be different if we use more teams. It’s also pretty relevant that Charlton aren’t actually very good; you might be getting regular game time at 20 years old in the Championship, but that may well be your level.

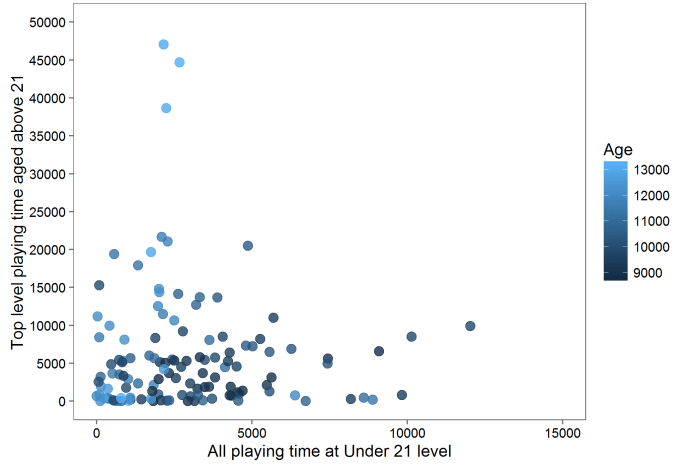

So I also had a look at Premiership youth team players at big clubs. I took the teams which have been in the Premiership the whole time (thus excluding recently successful teams like Manchester City) and relatively consistent performers – Arsenal, Manchester United, Chelsea, Liverpool, and Tottenham Hotspur. Whereas Charlton can give promising youth team players like Ademola Lookman a decent run (get your hands off him, please, we’ve got to escape League One again), it’s more of a risk for these larger teams to play untested potential over proven performers. The dilemma outlined at the start is more pressing for the big teams, so they (presumably) have more of a vested interest in solving it.

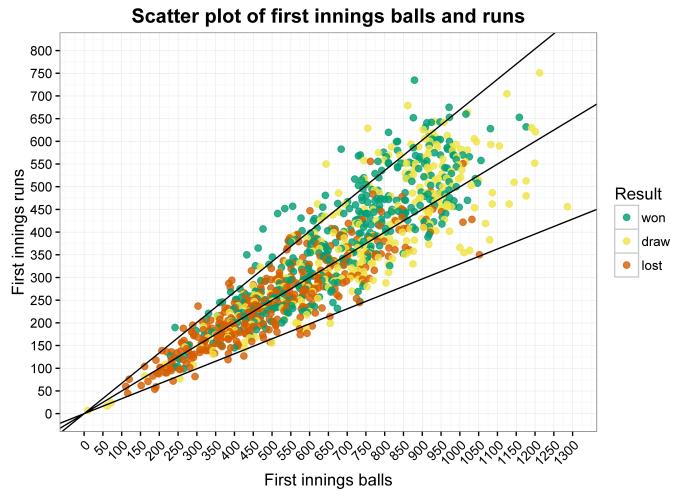

So is there a relationship between under-21 appearances at all levels and career success as measured by post-21 top level appearances?

…no. This time I’ve excluded players with zero appearances on either of the two axes because it was messy, and because there’s enough data points to look at players with both. There’s still no correlation at all (r = -0.06, p = 0.48).

Again, the same goes for actual playing time (r = -0.03, p = 0.72).

This still feels counterintuitive to me, but the data is clear: there’s no relation between game time as a player under 21 and later career success, whether you started at a poor Championship team like Charlton or a consistent big Premiership team.

This doesn’t mean that sending players out on loan to smaller clubs is actively bad for their development. Nor does it mean that keeping young players in the squad at the expense of playing time is better for their development. Rather, what it shows is that developing a young player is dependent on all kinds of factors, and that simple game time is no predictor of later success. When deciding whether to send a young player out on loan or keep him around the squad, club and academy managers should keep in mind that there’s no general tendency for either decision to be the correct one, and what’s best for one player will probably be completely different from what’s best for another.